Monthly Archives: March 2015

Listening Cherry 05 - Speech perception - phoneme input

I don’t read sufficiently regularly the research into psycholinguistics of listening. Part of me feels that I should read it constantly, particularly the research into speech perception, as it is the research field which is the closest to my concerns in English Language Teaching. However, I do jump in and read around occasionally, and when I do, I am reminded each time about the number of emotions that I felt on previous ventures into this literature: disappointment (at myself), awe, wonder, and unease .

The first is one of disappointment at my own ignorance - I wish I could understand better what I read, particularly as I feel there ought to be something of real importance for ELT in this field.

The second emotion I feel is awe at the ingenuity of experimental design, ‘Wow, you thought of doing that!’, and awe (again) at their rigour of their research methods - ‘Wow, you have these techniques, and this equipment!’. The third emotion I feel is that of wonder at the findings - typically ‘Wow, you make these small changes and you get these amazing results!’

The unease I feel is that it seems to me lot of the research is not addressing sufficiently the nature of spontaneous speech. Maybe I am just reading the wrong sort of stuff. At the risk of making a complete idiot of myself, here are some thoughts about what I have read recently.

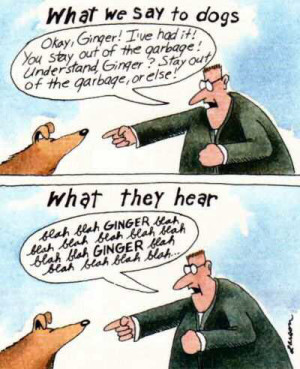

Crudely put, ELT places a tremendous amount of emphasis on top-down effects and strategies (‘native speakers don’t listen for every word, so you don’t have to’) whereas speech perception research places a tremendous amount of emphasis on the detail of how words-in-the-stream-of-speech are recognised. We in ELT have typically avoided getting to grips with the messiness of the sound substance that our students have to cope with if they are to become competent listeners. Instead we focus on the top-down stuff (because it is easy to do). We do loads of schema activation (‘think about your favourite pair of shoes’) and contextualisation (‘listen to this lazy person and this active person speaking about what they like to wear when walking’) and prediction (‘what do you think each one might say about the importance of good footwear’) and we get the students to use contextual knowledge to bridge over the decoding gaps to arrive at the right answers.

Speech perception research on the other hand has a history of a strong focus the the details of the mechanisms by which we recognise individual words in the stream of speech. Some of the models of speech perception belong to a paradigm which can be characterised as the ‘activated-candidates-in-competition’ paradigm which operates using what Magnuson et al 2013: 21 refer to it as ‘the phonemic input assumption’.

The phonemic input assumption ‘works’ by matching phonetic events in the acoustic substance (stream of speech), to phonemes, to words in the listeners mental lexicon.

So, for example, let’s say that a phonetic event occurs (low back vowel), then the phoneme |ɑː| is identified, and the following five words are then activated at that precise moment: are/art/artist/artistic/artistically. They are activated because they all begin with the identified phoneme |ɑː|, and these words are in competition, they are all candidates to be the target word. As each successive phoneme is identified, words either stay in or drop out of the competition depending on whether they possess the next phoneme. So let’s say that the next phonetic event leads us to identifying the phoneme |t|, giving us |ɑːt| the word ‘are’ drops out of the competition, and when the third occurs |ɑːtɪ| then ‘art’ drops out of the competition. This process continues until all but the target word emerges. This is a gross simplification, but it will give you an idea of the features of models which exist in the activated-candidates-in-competition paradigm. As Magnuson et al (2013) make clear, this is a starting assumption which makes research possible, it is not a research finding.

To be continued.

Magnuson, J. S., Mirman, D., & Myers, E. (2013). Spoken Word Recognition.The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Psychology, 412.

Listening Cherry 04 - The decoding gap

(Photograph by Glyn Owen.)

[This post follows on from Listening Cherry 03]

One of the aspects of Mirjam Ernestus’s work is her focus on the different soundshapes that words can have. And in particular on various levels of reduction. Her classic examples are (for English) yesterday being yeshay |jɛʃeɪ| and a little while being ud.l.wa |əɾl̩wa| (for more examples in English, Dutch and French cf. Ernestus and Warner 2011, p. 254). Of these examples Ernestus makes the following two points:

speakers are typically not aware of such variants in their own speech or in the speech of others, and … they do not recognise these variants when presented out of context (Ernestus, 2014, p. 11)

The first point, that speakers are not aware of the soundshapes they utter, is in line with my findings, and results in a phenomenon that I refer to, in Phonology for Listening as the ‘Blur gap’ (Cauldwell, 2013, p. 17).

The justification for her second point - that native speakers don’t recognise reduced variants out of context - comes from experiments reported in Ernestus, Baayen and Shreuder (2002) where they used a mixture of high medium and low reduced forms of Dutch words in three contextual conditions of decreasing size:

- in the full sentence forms,

- with vowels and ‘intervening consonants’ of neighbouring words,

- in isolation.

They found that

Participants recognised the tokens with low or medium reduction more than 85% of … [cases] independently of how much context they heard.

But with the highly reduced words, the recognition rate decreased dramatically in line with a decrease in context:

Highly reduced word recognition

| Context | Percent recognition |

|---|---|

| Full sentence | 92% |

| Neighbouring vowels | 70% |

| Isolated | 52% |

The table shows that where informants were presented with the full sentence context, they recognised the highly reduced form in 92% of cases, with the neighbouring vowels context this figure dropped to 70%, and in isolation, it dropped to nearly 50%. Ernestus (2014, p. 12) speculates that

listeners unconsciously reconstruct reduced variants to their unreduced counterparts on the basis of context [emphasis added]

That is, a speaker-created, speaker shaped stream of sounds arrives at the ears of the listener who immediately - way below the level of awareness - associates the reduced variant with its full counterpart, and believes that he/she has heard the full form.

This speed-of-light reconstructive perception on the part of native speaker and expert listeners is an obstacle to teaching listening to fast (normal) spontaneous speech. Why? Precisely because it is unconscious - it happens below the level of awareness - and we (expert-listener) teachers/textbook writers/teacher-trainers believe we hear full (ish) forms when in fact the sound substance consists of fast moving word-traces in a continuous blur. On the other hand, our students hear the mush of reduced forms for what it really is - an acoustic blur - because they have yet to achieve the unconscious ability to reconstruct words from the input of sound substance.

This results in the awkwardness and discomfort that often occurs in the classroom when recordings of real normal speech are played: teachers are deceived - by their own expert perception - into believing that the sound substance is unproblematic, whereas learners with undeceived honest ears hear the mush for what it is (an acoustic blur). And they have difficulties matching the mush with what they know.

So there is difference in perceptions of ‘what is actually there’ in recordings. Hence the awkwardness. This is a situation I describe (Cauldwell, 2013: 255) as the decoding gap.

Cauldwell, R. (2013). Phonology for Listening. Birmingham: Speech in Action.

Ernestus, M. (2014). Acoustic reduction and the roles of abstractions and exemplars in speech processing. Lingua, 142, 27-41.

Ernestus, M., & Warner, N. (2011). An introduction to reduced pronunciation variants. Journal of Phonetics, 39(3), 253-260.

Ernestus, M., Baayen, H., & Schreuder, R. (2002). The recognition of reduced word forms. Brain and language, 81(1), 162-173.

Listening Cherry 03 - Ernestus - word cloud

Mirjam Ernestus.

Last year I attended a phonetics workshop at Cambridge University where the main speaker was Mirjam Ernestus. One of the wonderful things about her research is that she works with recordings of spontaneous speech across a number of languages (Dutch, English and Spanish are just three of them). Another wonderful thing is that she is really interested in reductions of the soundshapes of words, e.g. ‘yesterday’ sounding like ‘yeshay’ - some examples are available here.

In the early weeks of this year I set myself the task of seeking to understand her 2014 paper ‘Acoustic reduction and the roles of abstractions and exemplars in speech processing.’ Lingua 142, 27-41. (Available from her website here all references below are to the pagination of her website version). I thought it would be a matter of a couple of hours reading, but actually there was so much to learn and so many other papers to look at, that it took me much longer.

I had hoped, in my reading, to find that psycholinguistics had ‘cracked’ the way that L1 listeners perceive and understand words in normal spontaneous speech, with all its reductions. But apparently not - Mirjam Ernestus tells us that the field is only beginning to address the this issue:

This phenomenon of acoustic reduction has received very little attention in the linguistic and psycholinguistic literature so far (p. 1).

and later

…none of the existing models of speech comprehension can easily account for reduced speech without additional assumptions (p. 13)

So what are these ‘existing models’? She divides the different models into two categories: abstractionist and exemplar-based. The two categories of model have different approaches to the mental lexicon, that part of the brain that stores words - their graphic shapes, their sound shapes, their meanings. The abstractionist model holds that the brain stores just one representation for every word (in the case of speech production and reception it would be an abstract version of the citation-form), and that reduced forms are dealt with by general processes that apply not just to the single word, but to many words.

The exemplar-based models hold that the brain stores many representations for each word (in my terms, many different soundshapes):

… the mental lexicon contains may exemplars of every word, together forming a word cloud. (p. 3).

What I have written is a gross simplification. But I like the idea of a word cloud. I think presenting many different versions of the soundshapes of a word in a clickable format (see, click, hear) would be a nice learning device.

[To be continued]